January 31st 2026 Seminar

A Philosophical Inquiry

How is it going everyone? I want to thank you all for coming and supporting local philosophy. Today we are going to do what they have been doing since Ancient Greece, which is getting people together in a room and hashing out philosophical ideas.

The Münchhausen Trilemma

First of all, how can we even know anything at all? Most people would agree that, yeah, we can't know anything with 100% certainty. But how do we even know something is likely to be true? How can we even have 51% certainty? You might say things like science. Okay… but how do we know science is true? You can't scientifically verify science itself. That would be circular logic. You can't use Occam's razor to prove that Occam's razor is usually true. You can't prove induction with induction. Induction is the idea that the past has any effect on the future at all. We have always observed that induction works. Always. But you can't use that fact to say that induction will work in the future, because you would have to be assuming induction. Because you are using past observation to say something about the future.

What about logic? You cannot use a logical argument to justify logic, because, again, that would be circular reasoning. So if you can't even justify logic, what are we left with? You wanna say "I don't know anything". But you can't say that because it implies that you KNOW that you don't know anything, which is a contradiction.

So basically, if you want to believe in logic or anything at all, it ultimately has to come down to an assumption. Or maybe you have a different solution to this problem. If so, I'd like to hear it, either email me or come talk to me afterwards. But for the rest of this talk, we are just going to assume that you have the knowledge of what the words I'm saying right now even mean.

The Nature of Morality

Concerning morality, we know that good an evil must exist, even if subjectively. Pain exists, and pain is just an arrangement of neurons. And if you really believe that pain truly does feel bad, then you have to admit that "badness" is a physical thing that exists in the world.

That is not to say that the ONLY place where good and evil is found is within consciousness. I think pleasure and pain clue us into what is actually good and evil, albeit imperfectly. What is good and evil more generally? I would conjecture that goodness is just statistical complexity, which is a thermodynamic property. Good and evil evolve in nature, altruism is an emergent property. And complexity tends to produce more complexity as life expands.

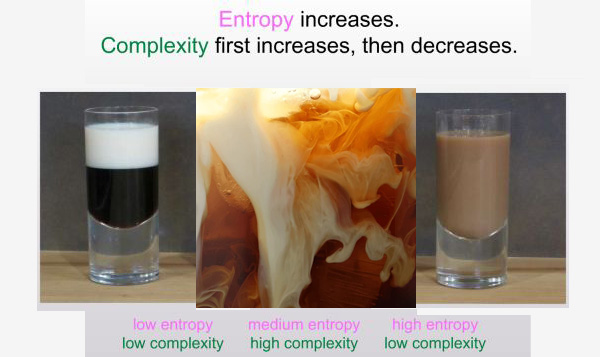

What is statistical complexity, exactly? Imagine you start with a cup of coffee, the top half is milk and the bottom half is coffee. Then it mixes together, and ends with an even mixture. Although entropy is always increasing throughout this, the complexity goes from simple, to complex, back to simple.

Same with the universe. It starts with the big bang, then there is maximum life, and then there is the heat death of the universe. Low complexity, then high complexity, and back down to low complexity. Admittedly, I don't have an airtight argument for this yet. So, this is my just my conjecture.

Free Will

But what is the point of objective morality if there is no moral responsibility? What if there's no free will?

Some people say that there is no free will because: All of your decisions are determined by your desires, and you never chose what those desires were. Even if you did choose a desire, you had to desire to make that choice in the first place. Eventually it always traces back to a desire that you did not choose. So according to cause and effect, all of your actions are ultimately caused by something that you did not choose. Therefore, no free will.

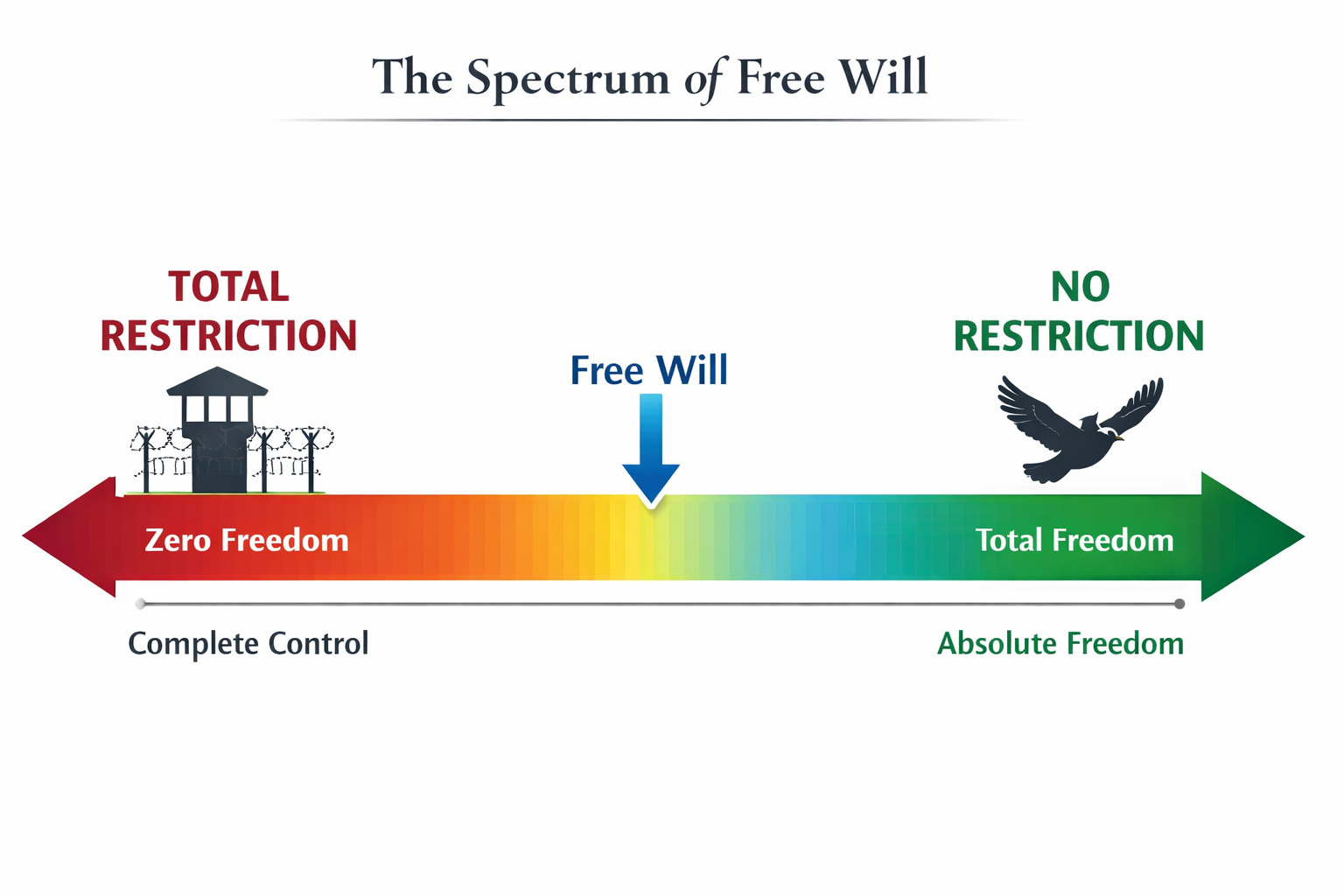

Here's the thing: it's true we can't choose our innate desires. And this IS a restriction on us. But it is not a 100% restriction. There are still further restrictions, and the obvious example is coercion. Let's say you're trying to decide between chocolate or vanilla ice cream. There could be more restriction if someone came in and say "No, actually I'm going to force you to eat this bowl of sand".

Free will means your will is free. Free from what? Free from restrictions. Not free from all restrictions, because that would be omnipotence, it just means having any freedom at all.

Now there is a spectrum of restriction and freedom. So where is the point that you say anything here and above counts as free will? That's just the line between voluntary and involuntary action. And even people that don't believe in free will would say there is a difference between voluntary and involuntary actions.

If you say that our will is not free, then you have to say that someone being coerced is just as free as someone making a voluntary decision. At that point you are just redefining what free means is in order to prove that free will doesn't exist.

Continue Your Philosophical Journey

Get the Free PDF: "Why Is There Something Rather Than Nothing?" + a link to join our online community